Ali, Activism & The Modern Athlete

Special | 1h 5m 4sVideo has Closed Captions

A Q&A with Raina Kelley (moderator), Malcolm Jenkins, Claressa Shields, and Ken Burns.

Examine the nature of the modern athlete and celebrity through the lens of Muhammad Ali and today. The hour-long discussion features Ken Burns, two-time Super Bowl Champion and Co-Founder of Listen Up Media Malcolm Jenkins, two-time Olympic Boxing Gold Medalist, World Boxing Champion and PFL fighter Claressa Shields, and ESPN/The Undefeated Vice President and Editor-in-Chief Raina Kelley.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate funding for MUHAMMAD ALI was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by David M. Rubenstein. Major funding was also provided by The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations,...

Ali, Activism & The Modern Athlete

Special | 1h 5m 4sVideo has Closed Captions

Examine the nature of the modern athlete and celebrity through the lens of Muhammad Ali and today. The hour-long discussion features Ken Burns, two-time Super Bowl Champion and Co-Founder of Listen Up Media Malcolm Jenkins, two-time Olympic Boxing Gold Medalist, World Boxing Champion and PFL fighter Claressa Shields, and ESPN/The Undefeated Vice President and Editor-in-Chief Raina Kelley.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

Conversations on Muhammad Ali has Ken Burns and special guests exploring Muhammad Ali's life and legacy. The hour-long discussions feature clips from the four-part series.

Video has Closed Captions

A Q&A with Ken Burns, Justin Tinsley (moderator), Ibtihaj Muhammad, and Sherman Jackson. (1h 4m 57s)

Video has Closed Captions

A Q&A with Ken Burns, Lonnae O’Neal (moderator), Janet Evans, and Todd Boyd. (1h 10m 6s)

Video has Closed Captions

A Q&A with Ken Burns, Jesse Washington (moderator), Rasheda Ali Walsh, and Howard Bryant. (1h 4m 43s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- Hello, I'm Paula Kerger, president and CEO of PBS.

Thank you for joining us for what we hope will be an engaging and inspiring evening around our upcoming documentary, "Muhammad Ali."

We're delighted to host this evening's conversation in partnership with ESPN's "The Undefeated."

As Ken Burns, Sarah Burns and David McMahon have beautifully captured in their film, Muhammad Ali was an extraordinary figure both inside and outside of the ring.

In addition to being one of the greatest athletes of all time, he was a global advocate and activist taking on racial prejudice and religious bias and using his platform to challenge cultural and societal norms.

Throughout his life and career, he encouraged all of us to embrace one another and rediscover our shared humanity.

We're thrilled to have a distinguished panel with us to discuss Ali, activism, and the modern athlete, including Raina Kelley, who's editor of "The Undefeated" and will moderate tonight's conversation, Ken Burns, documentary filmmaker and longtime friend of PBS, Malcolm Jenkins, two-time Super Bowl champion and co-founder of Listen Up Media, and Claressa Shields, two-time Olympic boxing gold medalist, world boxing champion, and PFL fighter.

This is the last in a series of discussions around Muhammad Ali and his extraordinary legacy.

You can find our previous panel conversations at PBS.org/AliEvents.

And of course, we hope you'll tune in for the premiere of "Muhammad Ali" on PBS on September 19th through your local station and on any PBS streaming service.

Thank you again for being with us tonight.

And now, let's take a look at the introduction to the film.

- You want some breakfast?

- I want some cornflakes.

- Can I have some of your cornflakes?

Oh, I don't want none.

I won't take none, I won't take none.

I won't eat none if you don't want me to.

Ooh, look at that pretty horsey.

- Where?

- Is that a white horse?

See?

No, stand up, look over there.

Stand up, you gotta stand up, over them hills.

See the big one, there he is.

(child gasping) What?

(man laughing) Where's the love?

(crowd cheering and chanting) - My earliest memories that I can think of as a child with my father are walking through airports and being in crowds and feeling the vibrations of people's clapping and shouts in my chest.

And just looking at my dad like, "Who is this person?"

And it was all the time, anywhere we went.

"You're the greatest, we love you!"

And the clapping and "Muhammad."

(Ali and crowd speaking in foreign language) - [Hana] I loved feeling all the energy and the love that he felt.

(crowd chanting) - We now think of Muhammad Ali as this vulnerable guy lighting the torch in Atlanta and everybody on the globe loves him.

Black people like him, white people, he's a universal hero, almost in a religious way, like the Buddha, but when he was in the midst of his career, and not just in the early bit, he was incredibly divisive.

- Boo, yell, scream, throw peanuts, but whatever you do, pay to get in.

- People hated him, whether it was along racial lines, class lines, Vietnam lines, political lines, religious lines, or they just couldn't stand him.

And people of course said the opposite.

And this was, "I loved him, loved him."

("Freedom" by Beyonce playing) But you had an opinion about him.

- I ain't scared to do battle.

It would take a good man to whoop me!

You can look at me.

I'm more than just confident.

I can't be beat!

(indistinct) And I'm pretty as hell.

Look how pretty I am.

(crowd laughing) My honed, trimmed legs and my beautiful arms and my pretty nose and mouth.

I know I'm a pretty man.

I know I'm pretty.

You don't have to tell me I'm pretty.

I'm cocky.

I'm proud.

Never talk about who's gonna stop me.

Ain't nobody gonna stop me!

I say what I wanna say.

Ain't no more big niggas talking like this.

("Freedom" continuing) - He was a pioneer.

He was a revolutionary.

He was a ground-breaker, a guy known simply as "the greatest."

- I am the greatest!

I've wrestled with alligators, I've tussled with a whale, I done handcuffed lighting and put thunder in jail.

You know I'm bad.

I can drown the drink of water and kill a dead tree.

This will be no contest!

Wait till you see Muhammad Ali.

- To have that chutzpah and to be a Black man in America was just outlandish.

- Muhammad means "worthy of all praises" and Ali means "most high."

And I just don't think I should go 10,000 miles and shoot some Black people who never called me "nigger."

I just can't shoot 'em.

I always wondered why Miss America was always white.

Santa Claus was white.

White Swan soap, King White soap.

White Cloud tissue paper.

And everything bad was black.

Black cat was the bad luck.

And if I threaten you, I'm gonna blackmail you.

(audience laughing) I said, "Mama, why don't they call it whitemail?

They lie too."

- I loved being around him.

I loved being around Muhammad Ali.

- [Ali] You gonna float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.

- Ah!

- Ah!

- Rumble, young man, rumble.

- Ah!

- Ah!

("Freedom" resuming) - The price of freedom comes high.

I have paid, but I am free.

♪ Freedom, freedom, I can't move ♪ ♪ Freedom, cut me loose ♪ ♪ Freedom, freedom, where are you ♪ ♪ 'Cause I need freedom too ♪ ♪ I break chains all by myself ♪ ♪ Won't let my freedom rot in hell ♪ ♪ Hey ♪ ♪ I'ma keep running ♪ ♪ 'Cause a winner don't quit on themselves ♪ (sound of blows landing) (upbeat R&B music) - [Narrator] He called himself "the greatest" and then proved it to the entire world.

He was a master at what is called the sweet science, the brutal and sometimes beautiful art of boxing.

Heavyweight champion at just 22 years old, he wrote his own rules in the ring and in his life.

Infuriating his critics, baffling his opponents, and riveting millions of fans.

At the height of the civil rights movement, he joined a separatist religious sect whose leader would, for a time, dominate both his personal life and his boxing career.

He spoke his mind and stood on principle, even when it cost him his livelihood.

He redefined Black manhood, yet belittled his greatest rival using the racist language of the Jim Crow South in which he had been raised.

Banished for his beliefs, he returned to boxing an underdog, reclaimed his title twice and became the most famous man on earth.

He craved adulation his whole life, seeking crowds on street corners, in hotel lobbies, on airport tarmacs everywhere he went, and reveled in the uninhibited joy he brought each adoring fan.

He earned a massive fortune, spent it freely and gave generously to family, friends, even strangers, anyone in need.

Service to others, he often said, is the rent you pay for your room here on earth.

Even after his body began to betray him and his brain had absorbed too many blows, he fought on, unable to go without the attention and drama that accompanied each bout.

Later, slowed and silenced by a cruel and crippling disease, he found refuge in his faith, becoming a symbol of peace and hope on every continent.

Muhammad Ali was, the novelist Norman Mailer wrote, the very spirit of the 20th century.

- I'm always gonna be one Black one who got big on your white televisions, on your white newspapers, on your satellites, million-dollar checks, and still look you in your face and tell you the truth and 100% stay with and represent my people and not leave 'em and sell 'em out because I'm rich.

And stay with 'em, that was my purpose.

I'm here and I'm showing the world that you can be here and still free and stay yourself and get respect from the world.

(bell dinging) - My name is Raina and I am so happy to welcome you here this evening to talk about Muhammad Ali.

And I wanna also offer some thanks to our esteemed panelists.

And I'm going to do that by starting right away.

I'm not even gonna give you a minute to think about a question.

This is a man whose life was that of American mythology.

Each one of you have had in your lives or are experiencing this moment of fame.

My question is for you.

Why is it so difficult for people to see a famous person, an accomplished person's humanity?

So even while we think about Muhammad Ali as the greatest, we still struggle to think of him as a man.

Do you find that in your own lives in having to represent all these different factions?

I don't know who wants to start with that one.

- Well, Raina, let me just say, because I thought that's a wonderful question and so original and so thoughtful.

You just saw the introduction to the film and you saw the opening scene of him stealing cornflakes from his child.

Anybody who's been a parent knows what it is to steal food from your kids and have them look away.

And it's a human thing.

And that was safely in the middle of our third episode.

And I had wanted to import it to the beginning to accompany and protect Hana, one of his daughter's first comments about just feeling the stuff, and the reason why is that we wanted to humanize him first.

I think the problem is that we move from being human beings to being boldface people, and we lose a sense of self, and we as the audience lose a sense of relationship to who they are.

They're suddenly bigger than us, or we're bigger than them.

And there's no communication in this world except among equals.

And so I think one of the reasons why we wanted to do this film, and the "we" is Sarah Burns and David McMahon and I, and they are the authors of the script, is that we wanted to take a comprehensive look at him, not just focus on the fights when he's already in a rarefied space, not just concentrate on the controversies of the Vietnam War or his religious conversions or whatever it might be, but to take the whole of him and across the arc of his whole life.

And that was an attempt to return to him, but also to us at the same time, a sense of his humanness, which is always denied if he's on a pillar or someone is looking down.

- Yes, that's so interesting.

Always denied.

And Malcolm, Claressa, is that something that you feel or have felt in expressing some of your greatest talents or needs or becoming boldface names?

- Well, it's different for me because I'm a woman, right?

And I'm a woman boxer.

And I came up, and Muhammad Ali is one of my biggest advocates.

He's the reason I am so outspoken and I'm so true to myself, but there are a lot of athletes who don't have that kind of role model.

And Muhammad Ali was the biggest role model to me.

And that's why, me being who I am, I call myself the GWOAT.

I only added the W because Muhammad Ali will always be the GOAT.

Nobody will ever come before him.

And so with me having him as my role model, that makes me feel okay to speak out, to talk trash as a woman, to be a boxer, to still stay close to my community, to have that heart, even though people will throw out insults at you because women don't talk like this, women shouldn't do this, women shouldn't do that.

And that's how it was for Muhammad Ali coming up.

Oh, Black men don't do this, Black men don't talk like that.

But Muhammad Ali was like, "Look, I'm gonna do whatever I wanna do when I wanna do it."

And it really takes a whole lot of heart to do that.

And I'm happy that I was introduced as a young child to him, because that's how I do my boxing career and my MMA career.

Look, I'm the greatest woman of all time.

And even though the world may not believe it, or some people may not believe it, every time I fight and every time I step out there, every time I speak, you're gonna know that I'm in the room and that I'm important and that I love boxing, but I also love Flint, Michigan, where I'm from, and I'm just gonna always be myself.

But sometimes being a celebrity and having so many people look at you and try to tell you who you should be and how you should be, it really does make people change.

And money is a big part of it.

Being in the limelight is a big part of it, being a role model, wanting to be a good role model is a big part of it.

And it really takes a lot of heart to just say, "Yes, I'm all those things, but I'm not a perfect person, and I'm still me at the end of the day."

And being yourself is the easiest way to be.

And that's why I feel like Muhammad Ali just stood in his light and never let nobody take that from him.

- That's beautiful.

Actually, I want everybody to remember that because I feel like that's a key.

Malcolm, how do you do it?

You've had some... - Yeah, I think especially in football, people look at it like we're in a gladiator sport in which everybody sees you as these superhuman type of athletes that perform on the highest stages, under the most pressure.

And they forget that we still have families, we still have feelings, and we still come from a lot of communities that are struggling right now.

We come from a people, right?

And when we get on these platforms, we're not just there to represent ourselves all the time.

We're carrying the torch for everybody that we represent.

And when we look at somebody like Muhammad Ali, it wasn't just his own family, Black people, but he represented this country oftentimes on his own back.

And so a lot of that responsibility, in the midst of all of the fanfare, we forget that we are actually human beings.

And I think Muhammad Ali was a great example of somebody who never allowed us or the pressure that we put on him to change who he was.

His ability to live out loud and in the fullness of just the entire spectrum of his humanity from flaws to his strengths was something that's been inspiring, I think, to athletes generations past, especially somebody like myself and team sports especially.

As an athlete, you're told to belittle yourself, to be humble, to not rock the boat, but it's like, no, we can be athletes.

We are the best in the world at what we do.

We have that skill level, but we have the right to be just as much a human being or to be just as much ourselves as anybody else, regardless of what standards that people are putting on us.

I know he's been a great example for me when I'm trying to navigate all the things that I'm going through as an athlete who's vocal, who has a voice and dares to use it.

He's one of those north stars that gives you a roadmap on how to navigate it and understand what's gonna come with it as well.

- Yeah, I love that use of the term north star, and I'm gonna use that, Ken, to ask you to introduce the next clip because you know, consequences, right?

- Yeah, you're right.

It's just perfect because both Claressa and Malcolm echo the last comment of Muhammad Ali in the introduction about representing and being yourself, and then this next clip is also the courage it takes.

This is a film about freedom, and it's really difficult for a Black person in America on this continent to escape the specific gravity of what's laid on top of them.

And he did and did not forget where he came from, but it also had consequences.

So at the height of his professional career, when he is indisputably the greatest, he is the greatest boxer of all time, certainly the greatest athlete of the 20th century, he is reclassified as unqualified for the draft for Vietnam, but now classified as eligible to the draft.

He is drafted.

Because of his Muslim faith, he has refused the draft.

In America, a Black man doing this is seen not as a religious act, as an act of faith, but as a political act.

And so all the opprobrium is heaped on him, and he's going to go on trial for refusing the draft.

And so I wanted to drop you into a moment in our second of four episodes where we are beginning to see this, but there's also, there aren't reinforcements, but there are other people in the country who respect his stand.

A lot of people are reviling him.

He's at his most divisive.

He's been outspoken.

Strike one.

He's joined the Nation of Islam.

Strike two.

And now he's refusing induction into the army.

Strike three.

But there are people around.

Cesar, let's run this next clip, and we can come back on the other side of it.

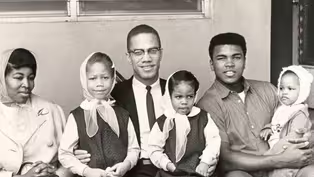

- [Narrator] On June 4th, 1967, Jim Brown, the retired football star, convened a closed door summit of Black athletes in Cleveland.

They invited Muhammad Ali in hopes that he might entertain a back-channel offer from President Lyndon Johnson that would keep him out of jail and in the boxing ring.

(smooth jazz music) - Number of the participants were members of the Cleveland Browns, Bill Russell was there, myself, and a few other people who were related to sports, but we all wanted to just see what Muhammad Ali was all about with regard to his stance on Vietnam.

- [Reporter] Jim, what do you could think of the possibility of the champ going to jail, and how do you feel about the image this might create among Negro athletes?

- Well, as you know, religion is based on belief.

We all have various religions in here.

And once the champ convinced us that it was solely a religious matter and that he believed completely, then I had to leave it at that and give him respect as far as his beliefs.

- And we were unified.

We stood behind him.

We wished him success, but there was nothing that we could say formally that was gonna mitigate what he had to go through.

- [Narrator] "I'm not worried about Muhammad Ali," Bill Russell said.

"He is better equipped than anyone I know to withstand the trials in store for him.

What I'm worried about is the rest of us."

- All the light in the room focused on him, it seemed.

He attracted light.

That was who he was.

And I saw in Muhammad Ali's character the willingness to take on the burdens of all Black Americans in confronting the racism that we all have to deal with.

He was willing to take that on.

And I wanted to support him in that.

To me, it felt just like I felt about Jackie Robinson.

I watched him when I was a little boy and it seemed to me that Muhammad Ali just up that mantle.

- [Narrator] Two weeks later, an all-white Houston jury found Ali guilty of refusing the draft.

The judge, ignoring the more lenient recommendation of the prosecutor, sentenced him to the maximum: five years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

And he would have to surrender his passport.

(tense music) Ali's lawyers immediately filed an appeal, prepared to go all the way to the Supreme Court if necessary, a process that could take years.

Ali remained free, but without his title or a license to box.

He fully expected that he would one day go to jail for his beliefs.

- We who are followers of Elijah Muhammad and the religion of Islam, we believe in obeying the laws of the land.

We are taught to obey the laws of the land as long as it don't conflict with our religious beliefs.

- [Reporter] Will you go into service as such?

- This would be 1,000% against the teachings of the honorable Elijah Muhammad, the religion of Islam and the holy Quran, the holy book that we believe in.

This would all be denouncing and defying everything that I stand for.

- [Reporter] This would mean, of course, that you stand the chance of going to jail as a result of not going into service.

- Well, whatever the punishment, whatever the persecution is for standing up for my religious beliefs, even if it means facing machine gun fire that day, I will face it before denouncing Elijah Muhammad and the religion of Islam.

I'm ready to die.

(tense music) - When I think about him saying, "If they wanna put me before a firing squad tomorrow, I'm ready to die before I abandon my religion."

That's it.

You can't teach that kind of thing in lectures and books, that kind of thing has to be modeled.

And models turn into traditions and traditions provide people with the mechanical memory to do the right thing.

That's what Muhammad Ali represented in that moment.

Anybody now faced with a major decision, and what's the right way is clear and the wrong way is clear, but the consequences are dire, now they have a model that they can fall back on psychologically, emotionally, spiritually.

That's what Muhammad Ali represented in that moment.

And to me, that moment will live on forever.

- Inspiring.

And I wanna get, again, right to it.

I'm going to start, Ken, with you.

We call now "cancel culture."

What is it that we are talking about?

What was happening then?

What is that shift in America from then to now?

- Well, I'm not sure that it is different, except that the stakes here are so high.

The risk is so extraordinary in the case of Muhammad Ali.

He is at the peak of his career, as I said, and if this is a film first about freedom, it's also a film about courage.

As you can see, this willingness of this young 20-something year-old kid facing down the entire United States government in support of his religious beliefs and becoming a pariah hated not just by white people, but by Black people too, who were threatened by the choice of religion, who were threatened by not serving in the United States army.

He's not sufficiently grateful, it appears to many people at that time.

I think we can put it in context.

There are lots of athletes who are speaking out and a few over time have risked everything.

Smith and Carlos at the '68 Olympics raising their fist.

They were disappeared.

Curt Flood, a Black man in baseball, challenging the plantation system of the reserve clause that enslaved not only Black but white players, since the beginning of the professional game, he's disappeared.

It would take some white guys, Messersmith and McNally, and Marvin Miller, the labor leader, to liberate everyone from the reserve clause and create the great, wonderful baseball era that has been since then.

Colin Kaepernick isn't throwing a football professionally at the level that Malcolm is playing, but he does have a Nike contract.

This guy, Muhammad Ali, was living off his second wife's college fund in order to survive and had to pivot into speaking to college campuses.

This was sacrifice.

And as he said, he's willing to face machine gun fire today.

That's something amazing.

And so I think there's almost a luxury in the cancel culture that we have today, in that it is an arbitrary and sometimes capricious device of the unseen and unlabeled mob and not the place where someone stands in front of authority.

it's like the guy in Tienanmen Square in front of the tank.

This is Muhammad Ali.

"No, I will not go," right?

And what it provides, as we've heard already to Malcolm and Claressa, is, as Sherman Jackson just said, it provides the muscle memory of what to do when you're faced with a decision like that.

And to me, this is why his story is so enduring and why, even though he's a product of 60, 50 years ago, all of this stuff is happening, he is also speaking to us directly today.

And in fact, I don't imagine a time when Muhammad Ali won't be speaking to us and standing there as an inspirational model, as you yourself said, not just to the United States, but to the world.

This man dies the most beloved person on his planet.

Something happened between defying the war in Vietnam and that, and that's one of the reasons also that Sarah and Dave and I sought the comprehensive view of this story that we did.

- I think that this might be something that Malcolm and Claressa can help us with, because Malcolm, I'm gonna start with you.

You are an excellent football player.

You are also a Black man.

Do you ever get a sense, do you have an understanding of why sports plays this role in our freedom, in our social justice movement?

Your position as an athlete, what has that given you that, say, another Black person in a boldfaced name does not have?

- I think one of the things that sports and athletes and entertainers have is the ability to reach everyone.

When you go into the stands of an NFL game, there's people from all races, all backgrounds, everything.

Everybody convenes around our sports, our talent.

And so as athletes and entertainers, we have this unique ability to convene people.

And when you have that power, you have the ability to influence, right?

When you make it more than just the game, which is what Muhammad Ali did, if you followed him, you're going to get boxing, you're going to get him.

And that meant dealing with all of the things that were on his mind, that were on his heart.

And the thing that I think is most inspiring about Muhammad Ali, at least for me, is that most athletes don't know how to function outside of their sport.

if you threaten to take their sport away, they don't know who they are outside of being an athlete.

And he knew who he was, and sports were just his platform to show the world and bring a message to everyone, because they wanted to come see his talent.

You wanna come see his talent, you had to deal with the rest of the message.

And I think that's one of the things that, that example was shown to athletes like myself, Colin Kaepernick, and all of these athletes that you're seeing now that are leveraging the movement, the notoriety, and all of the eyes that are on athletes, is that we realized, once we get over the fear of losing our sport and realize that we're actually bigger than what we can do with a ball, what we can do on a court or in a ring, and now people are coming to see our talent, then we control how we want to present ourselves to the fans.

And I think Muhammad Ali, at the same time that he was the greatest fighter in the world, was also one of the great orators of the Black experience and was able to bring a certain language to a world viewership about a Black experience that people can relate to.

And I think that unique function in this struggle for equality and the Black plight is a significant one because it's the ability to quickly disseminate this information, this experience to a world audience that otherwise wouldn't get it.

- I'm gonna ask Claressa, because I think that you don't credit your own courage.

Not a lot of people are in, as you say, gladiator sports.

I think that there is some courage related to your talent in athletics.

Claressa, tell him, what do you think?

- What's the question I'm answering?

- Okay.

Do you think your ability in the ring, your ability to be the GWOAT, also makes you braver, makes you stronger, like Muhammad Ali, to speak your truth?

Or is that something that's in everybody?

Because these social justice movements start in many cases with athletes.

- I think that one, athletes are given a platform whether you want one or not.

When you become the best at what you do, it automatically gives you a platform and some people never use it for social justice, never use it for the people that need help.

And then there are the few who wanna get involved with politics, wanna get involved with giving back and helping their communities.

And it's a special kind of courage to call yourself the GOAT because I know that they called Muhammad Ali "the Louisville lip," before they acknowledged him being the GOAT.

Like "Oh, he talked too much, but he's not the GOAT."

And he went out there and proved that he was the GOAT.

And he spoke that before anybody spoke that of him.

So I think that all great athletes, we all had that defining win or that defining moment in our career where we're like, "This is it.

Nothing is disputed right now.

I'm the best right now.

And I'm gonna speak that.

I'm gonna give everybody that."

And for those who don't like it, you just say, "Well..." But I definitely think that boxing gave me a lot of confidence.

Me winning my boxing matches, me getting more notoriety, me going to the Olympics twice, being the first woman to win a gold medal and then to turn pro and be the first woman to fight on television.

And when I turned pro, it just was like, look, God has given me this platform not only to big up myself, but big up women boxing, big up women in sports, big up people from Flint.

We come from those areas that people consider places that people shouldn't be able to make it.

And I feel like I wouldn't have that confidence without my sport.

I really couldn't imagine boxing being taken away from me.

And Muhammad Ali turning down the draft and possibly about to be put in jail for three to five years, and having his title stripped, he was just a different kind of athlete and he's a once in a lifetime because I'm not gonna say that I wouldn't have did it, but it would have been hard for me to make that decision, especially knowing that they would have took everything away from me that I worked for, you know?

So he was a different kind of athlete, and I feel like boxing gave him that strength to speak it out.

But I feel like also, him being very religious and knowing the book of Quran, that it really gave him a special power to be able to endure the consequences of those things that he had to endure.

Because he just said, "This is what I believe in."

And to be able to say he's gonna stand there and you guys have to bring an army, shoot him down tomorrow, he's ready to die for it.

That's a different kind of courage, you know?

He was a different kind of man, honestly.

I've met any boxer you can think of, any man you think of, basketball player, football player.

And listen...

I was able able to meet Muhammad Ali too.

And I still haven't met an athlete with as much gumption as he had.

I just think he was once in a lifetime.

That's it.

Once in a lifetime man.

- Ken, once in a lifetime, you have covered some pretty big platforms, right?

What you're talking about- - We're talking about somebody on the level of Abraham Lincoln.

We're talking about somebody on the level of Louis Armstrong.

A once, maybe not in a lifetime, but once in a generation or millennium kind of person.

I think Claressa hit it really well.

The sacrifice, the opportunity to sacrifice is really something else here.

it's just one of the great American stories of all time.

- And yet he remains funny and human and approachable.

That is an endurance, that's not courage, that isn't resiliency.

When you were putting this film together, what did you see?

What was that through, that current there?

- He seemed to know from a very early age who he wanted to be, how he wanted to...

He put on boxing gloves and a few weeks later, he's announcing he's gonna be the greatest, you know?

There's all these signal things.

You couldn't pick one part of his life that you want.

He goes to Rome, he wins the gold medal.

Even the Russians love him.

He comes back, he beats Sonny Liston.

Every one of his collected fights is like the collected works of William Shakespeare.

You cannot describe the dramas of the first Frazier, the Kinshasa, Zaire fight with George Foreman, the third Frazier, the first Liston.

They're just filled with drama that you can't believe.

And that's just one part of his life, because I think what we're talking about, and everybody seems to be saying is, it's not just the talent.

He happens to be the greatest boxer.

But when we say "the greatest" about him, we mean a great human being, a great American.

This is not the way you're gonna argue about Michael Jordan or Tom Brady.

They're limited.

This is somebody who transcends the sport because he never forgot where he came from and continued to represent not just his people here, but anybody who felt the boot of the oppressor on their neck around the world, he spoke to them.

He was saying, "I am Black and I am beautiful."

And that last thing at the beginning of the introduction, at the very end of the introduction, before we go to round one, where he's pounding on the table and he's insisting that he got everything that he wanted, he got his freedom, but he didn't forget where he came from.

This is central to who he is.

- And again, where he comes from.

We often use that phrase.

In a lot of ways, for all of us, it is our blackness, right?

And in many ways, we cannot ever be allowed to forget that.

And the question is, when he put those gloves on, Malcolm, you suit up, Claressa, you're gonna go into the ring.

Do you have a sense that you are carrying on your shoulders not just your blackness, but all of ours?

You know what I mean?

Ken, for you, when he put on his gloves and said, "I'm gonna be the greatest," do you think he had a sense that he meant something bigger than boxing?

- Yeah, and I think it's like Jackie Robinson.

Sarah and Dave and I made a film on Jackie Robinson.

When he came out to play first base, this is the grandson of a slave, when he played first base at Ebbets Field on April 15th, 1947, Martin Luther King was a junior at Morehouse College.

Nobody had refused to give up their seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, nobody had had a lunch counter demonstration.

So Jackie had done both those things on his own, got court-martialed for the first and got in trouble in Pasadena for the second.

The military wasn't integrated.

And Brown vs Board of Education hadn't happened.

So you're seeing somebody who is actually leading the country out of it.

And when you think of the oldest picture of Jackie Robinson, it looks like he's 85 or 90.

He's 53 when he died.

And that's the load that he carried.

And every time he went up to bat, he was batting for everybody who had been denied a position, and also for everybody who was now going to be able to have a position and not just Black, but brown as well.

And the doors that he opened, Muhammad Ali is like that and then some.

- Malcolm, what kind of pressure have you taken out on the field?

You see what I'm saying?

Do you feel that?

- I think, for me, my experience is, I grew up loving to play football, right?

And then you end up being really good at a sport, and you're in a position in which you got cameras in front of you constantly.

For me, at least, I began to think about, "What am I using this platform to do?"

And then as things are going on in society, I realized there's an opportunity for me to insert myself.

But you asked a question before about, do athletes, because we're athletes, do we automatically have this toughness where we want to jump into the fight?

And I would say, no, we don't.

And even in my sport where we're looked at as gladiators, big, strong, 300-pound men in the locker room, there's not a lot of people that are volunteering to step up and do this kind of work.

It's not easy.

And Ali said it in one of the clips earlier.

He said, "I'm free.

(indistinct) But I'm free."

And that (indistinct) small one, that ability to be free to be unapologetically yourself, to not be hindered by your sport or an employer or anybody who could take anything from you.

You have no control over me with fear or anything like that.

That is absolute freedom.

But that comes out at a very high cost, especially from an athlete, You have to be ready to lose everything.

And I don't think that comes naturally.

So I think when we see leaders who are out there, whether it's your Alis or Kaepernicks and John Carlos, Tommie Smith, they're not just built different and athletes who are willing and able to run to the front line.

That's a conscious decision.

Every single time they open their mouth to talk about who they are, to talk about issues, every time that they put themselves out there, it's a conscious decision.

And it takes intentionality to really be out there like that, because that stuff is heavy.

When you talk about Jackie Robinson, how old he looked and weathered he looked after carrying that burden.

And oftentimes that responsibility is dropped on your lap once you hit the height of your career, right?

We didn't put this pressure on Ali as an amateur boxer or early on in his career.

When he became the GOAT is when almost a survivor's guilt or the responsibility to actually use your platform comes.

And not every athlete is ready for that.

And so I think to me, it means even more to watch those who come before me that dealt with a lot more pressure than we have, with a lot less voices in the ring with them, but also (indistinct) there's not that much to be afraid of, but we don't have to be afraid.

(indistinct) Imagining more Alis when Ali was around, how much further would we be as a society, how much further would we be as a people, if we had more of those who have the platforms to scream our experience from the mountaintop, do that when it's necessary.

We're continuing to fight that.

- Agreed, and we can say this knowing, sadly, how the Muhammad Ali story ends, right, which is 180 degrees.

I'm gonna ask you, Ken, to introduce our final clip but nobody does this for the ending, right?

Is there a more extraordinary story, starting from bigger than boxing and ending with larger than life?

- This is a great, great story.

We're gonna share a clip from the fourth of the four episodes.

Towards the very end of that, you'll hear the voice, but not see the picture of Jonathan Eig, one of his biographers.

And he's just at the end of his life.

I think the significant thing is that in the last three decades of his life, when he's more or less silenced by Parkinson's, and we tend to write it off, because in connection with the boxing life, it seems so constrained, it's where in many ways he had this exponential growth as a human being, but also in his reach in the world, even greater than before.

And so this is just a sense of looking into the last years of Ali and this extraordinary legacy.

- Ali late in life talked about this tallying angel, he called it, that there was an angel up there who counted all the good things you did in life and all the bad things you did in life.

And if you had more bad things than good things, you were going to hell.

And he had a very vivid impression of what hell meant.

And he acknowledged that he had a lot of negative marks, that the tallying angel was not going to be happy with the way he had treated women in particular.

(somber piano music) - [Narrator] 30 years after Ali first faced Joe Frazier, a reporter asked him about their long-running feud.

"I called him a lot of names that I shouldn't have called him," Ali admitted.

"I apologize for that.

I like Joe Frazier.

Me and him was a good show."

Frazier never forgave Ali.

Later, he expressed sorrow at having abandoned Malcolm X.

"Turning my back on Malcolm was one of the mistakes that I regret most in my life," he wrote.

"I wished I'd been able to tell Malcolm I was sorry, that he was right about so many things."

- Daddy evolved, he became better.

And daddy said, "I'm bigger than boxing."

That meant (delicate piano music) boxing was this much.

His evolution into the person he is today is way bigger than him just boxing.

And I think he knew that and he carried it with him, his love, and he gave it to every single person he met.

And I think that's beautiful.

- [Narrator] As the 20th century came to an end, Newsweek, Time and Sports Illustrated all named him athlete of the century.

In the days after the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001, American Muslims were the victims of hate crimes, simply because of their faith.

"I am a Muslim.

I am an American," Ali responded.

"If the culprits are Muslim, they have twisted the teachings of Islam.

Whoever performed the terrorist attacks does not represent Islam.

God is not behind assassins."

- What I hope is that Muhammad Ali will be a constant reminder to America of just how thoroughly American a believing, practicing, sincerely committed Muslim can be.

Whatever one's background is, Ali belongs to America, all of us.

And I think that he belongs to all of us because he affected all of us.

And I hope that that's part of the legacy that he will leave, that America won't forget Ali as this American Muslim, with equal emphasis on American Muslim.

- [Narrator] On November 9th, 2005, President George W. Bush presented Ali with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the United States.

That same year, the Muhammad Ali Center, a museum dedicated to his life and legacy, opened in Louisville.

- Muhammad Ali was an activist who fought to reach us a certain way and to move America in a certain way, to move individuals in a certain way.

"I'm going to take this path.

I believe that I'm right.

And even if I'm not right, I'm still me."

And to be able to follow that and to know that there was going to be an enormous price to pay for that, and to have that be generational, to have that live on beyond you, is extremely valuable.

Everything that he did couldn't be undone.

- I'm gonna ask question, Ken.

Does "more than an athlete" start right there?

Boxing was the beginning of an evolution.

Does he begin to change the meaning of what it means to be the GOAT right there?

- At what point?

At the end there?

- Yeah.

As he's looking at the evolution of his life.

Yes, he's looking back.

- Raina, there's some places early on when he's just a kid where you see who he is.

You feel it a little bit in Rasheda because she carries whatever DNA of his that he had, that goodness, that love, that capacious heart.

But I think it was there from the beginning.

And of course the trials, all of these difficulties hone and sharpen and focus this greatness.

And then I think, as I said in introducing the clip, there's a tendency to write off this last period because he's not doing what we think Muhammad Ali should be doing.

But I think this last period, difficult for him to adjust to, was nevertheless him realizing that this was exactly what he should still be doing and found in his silence another and perhaps even louder voice.

And I love that.

You know Michael J.

Fox, who suffers from Parkinson as well, said, "I couldn't be still until I couldn't be still."

And I think there's an analogy that this wonderful, voluble man that you never want to have shut up because he's so beautiful and he's so funny and he's so generous and he's got poems and he's got quips and he's quick and he's sharp and he's smart.

But also, when he can't do that, he's as powerful as he was before.

And maybe perhaps even more powerful because he endures.

And that's part of that human statement that he makes.

That's why when, as David McMahon says, when he would do a news conference, the sporting world might stop.

When he goes to Pakistan, the whole country stops.

- Malcolm, you're moving on to other phases of your life.

You're doing other things.

You have founded companies, organizations, paying it forward.

Where's sports in your life now compared to where it's been, and how do you feel like it's affecting you, your voice and your ability to be you?

- I think as a young athlete...

I think everybody, every human being at some level is contemplating their purpose for being here.

And I think young athletes, oftentimes we put a lot of our weight into what we accomplish in our sport.

We try to set records, we try to go for wins and we want to be Hall of Famers in our scores because we want to be remembered.

We want to have done something meaningful with our effort.

We want it to be something that people will remember.

But the problem with athletics is, and I'm 13 years now in the NFL, as I've (indistinct) a little bit of my maturity level, you realize that every year a record is broken, every year, some new person is doing, so if you wasn't the first person to do it, nobody's going to really remember what you do as an athlete.

And if they do, great, but you start to realize that it's still not your entire purpose.

And then one of the things that athletes don't get an opportunity to do enough of is explore who they are as people, by what their other talents are outside of their sports.

What are their other interests?

What other impacts can they have?

And honestly, it wasn't until I stopped looking for what I did on the field to define who I was that I was able to really find a much larger purpose for myself outside of sports.

And now football for me is back to what it used to be for me when I first started playing, which is just what I like to do, not who I am at all.

Yeah, it's a small part of who I am.

And I think that revelation for me has allowed me a lot of freedom to be able to try other things, to start a production company, to get into writing, photography, design, things that you normally don't even get the opportunity to try, but you realize that, "Oh, I do have interests and skills outside of my sport."

And those are things that people cannot erase, right?

Nobody's gonna come replace what Malcolm Jenkins has been able to provide to the earth because there's only one of me.

And I think that mentality is something that comes with a little bit of maturation, but one that we need to talk more about to our younger athletes, that you wanna be known for what you do in your sport, for sure.

If you've got that talent, exploit it for yourself to its brim.

But what you do in your sport does not define or is not the end of your legacy on this earth, and most times it's just a launching pad.

And it's been fun, you know, I'm in those golden years of my career where I'm active, still at the top of my game, and I have that mentality.

That's a hard place to be.

Most people are already out of their sports when they realize it, or aren't at the top of their game.

And I find myself in this sweet spot.

And it's interesting to see how it plays out.

- Endurance, courage.

That's how it plays out.

Beauty, gorgeous talent.

Same, actually, for Claressa also.

You knew him, you are in the same field.

Is there a connection between getting in that ring, learning to be so good at that, and also being able to make your life be about love, service, faith, belief, something bigger than you?

- I think everybody is different, and I don't know... Matter of fact, I do know.

I have a certain love for fighting, right?

That's why I do it.

I boxed and now I'm doing MMA and there's not a lot of people that can do that, that would train that hard to do those things.

But it's just the admiration inside of me that makes me wanna do it.

And that's why I've been so great at boxing and I wanna challenge the best.

And then MMA, I wanna become the MMA world champ in the next few years, but that's something deep down inside of me.

People don't have that admiration for fighting that I have, but that's something that I've learned to accept.

(laughing) I've learned to accept, I've learned to embrace it because when I try to turn it away, all it do is keep eating at me and keep eating at me.

So when I finally just was like, "You know what?

I love to fight.

This is me," and then I just put that energy out into the world, because it's different for me because I'm a woman, I'm not supposed to love physical contact.

I wanted to play football when I was younger also.

But my dad told me no.

(laughing) - So you became a boxer!

I love that.

And what did your dad say about that?

No.

I wanna ask an audience question.

And this is from Connie and I love this question.

"What do you think," it's for all of you.

"What do you think allowed Muhammad Ali to stay true to who he was, where he came from, in a society where sometimes we see," and then I'm gonna add, we make, "people change when they achieve fame or success?"

- There's really something deep down inside of him that kept him the same, the way he was able to withstand that kind of pressure is really about the kind of person that you are.

And I really think, even though he was young in his career, for him to have that cockiness about him and to say, "I'm the greatest of all time."

And he loved Sugar Ray Robinson, he loved Joe Louis.

He loved those fighters, but he had to speak it how he felt deep down inside.

And he spoke it, and those guys that came before him embraced him for that, even though they felt like, "Hey, we got a better jab, we got a better right-hand, we got a better this and that."

They still were like, "Yeah, you are the greatest because you spoke it" and they didn't speak that way.

So he wasn't just being a great boxer like them, but he was just being the greatest person of himself.

He wasn't like the guys that came before him or like those great fighters who were humble and who actually went to the draft and everything.

He just was like, "That's not me.

That's not what I wanna do."

And you know those people who would rather go to sleep knowing that they made the decision for their life, than failed to the pressures of making a decision because the world has made them make that decision?

And I'm one of those kinds of people too.

I like to go to bed at night knowing that even if I make it wrong, if I get a wrong answer, or I get the right answer, whatever the consequence is, I chose it.

It was me and nobody else, no matter what they say or how they do it, is gonna make me change my answer or how I answer something or how I feel because whatever the consequence is, give it.

The consequence or reward, it's all me.

That's how I've always lived my life when it came to decisions.

And I feel like Muhammad Ali was the same way.

- That's what it's been like for you, Malcolm?

Same?

- I would say the biggest thing, and sometimes we don't get to see it, but the biggest thing for me that has helped me deal with pressure, and I know when you go back and look at Ali's life, you start to see how he was able to stay focused and really bear all that weight on his shoulders, because he kept his ear to the people who he was trying to help, right?

He never cared about listening to the media or the naysayers, or even the Black people who didn't agree with him.

Even the summit of athletes, when they were in Cleveland, they were coming there really not to support him at first.

They were trying to feel him out and see where he was at when it came to the war thing.

And it wasn't until he convinced them with his own conviction, and then he got that support.

But for me, it's the small voice that you have around you that can let you know that you're going in the right direction, that the people who you're trying to fight for are with you and agree with you.

I've gotten those small whispers at events and calls from people.

John Carlos is a guy who calls me or texts me and just shoot me and say, "Hey, I'm proud of what you're doing."

And those types of things keep me going.

And I know having Malcolm X in his corner, being able to be that guardian angel to give you direction as you navigate this, 'cause as athletes, one of the things I did not really understand coming into it is that you are gonna go through life with very few roadmaps or guidelines.

Not many people can tell you what to do or where to go.

So when you do have those voices, it's a very significant and special thing.

And oftentimes people will get to see the athlete, but they don't see the support pass, or don't even know how much (indistinct) person on the sidewalk who tells you that they're proud of what you're doing, how much that affects the athlete or somebody who is standing and carrying that weight.

Those types of things keep me going and were motivating for me and I'm sure were motivating for Muhammad Ali.

- That brings us back, Ken, doesn't it, to the cornflakes moment from the intro.

What did you see?

What do you see that made him... - Well, it's hard to improve on what Claressa and Malcolm just said, because they really hit the essence.

In essence, Claressa is saying, "Here is this young person with an inner purpose that he's able to express in a way, and he can be true to himself."

And Malcolm is realizing that of course, there's gonna be help along the way and guidance and teachers and things like that.

So I would suggest that he was born with something.

And then I think he was also helped by the association.

There are many ways in which you can see the association with the Nation of Islam as problematic, but in one way, it's not.

It provides a curious and probably deeply disturbed young man trying to deal with race in America, the trajectory of his own life, his family's life, the whole history of being Black in America, and he finds a foundation that the Nation of Islam is able to give him, he finds it in the mentorship and the friendship with Malcolm X, at least for a while.

And that helps, I think, to crystallize whatever is in him from the beginning.

And those two things permit him to remain resolutely himself.

And so it was important for us to recognize the fact that as bold a name as you can get is Muhammad Ali in this world.

But that he is a father, that he is a man, that he is, as Malcolm said, deeply flawed, and the film does not flinch or shy away from examining those flaws.

But he remains this hero in the most epic sense.

And he takes the hero's journey, which is, of course, straying, of getting lost, of making mistakes.

But as Howard said at the end, doing it his own way, on his own terms.

And I think it's so beautiful there that as we cut away from Howard, we cut to a young woman on the Brooklyn Bridge in a protest that we're not telling you what it is, but what she seemed to feel was an adequate representation at that protest is to wear a simple black T-shirt with white letters that says "Muhammad Ali."

Just two words, "Muhammad Ali."

And that was enough to signal these themes of freedom, so difficult, of courage, almost impossible to exhibit at the level he did, and of love, which is what he spread his entire life.

And I love the fact that he lives on in Rasheda and he lives on in that woman.

And he clearly lives on in the exemplary example that Malcolm has given to us over the many years of his professional life, and as Claressa is doing right now.

And so that's him, you know, and he's gonna be around for us, whoever we are, when we need him, when we need to have a guidepost of where to go.

As Malcolm says, there's not too many roadmaps out there.

And at least now, having the life of Muhammad Ali behind us, we've got at least one exemplary direction that we can go in.

- And he was always still him.

I can't believe this hour just completely flew by.

And I absolutely mean it.

I have 15 more questions, but they're making me end.

I wanna thank each and every one of you, but Ken, I also wanna thank you for making this film.

This is somebody whose model, as you say, whose record, whose mythology, whose spirit needs to be seen.

And I wanna thank you, Malcolm and Claressa, for your talent and your coming here tonight, but also for what you will do and your respect and keeping your ear to the ground for the people who really matter.

Thank you so much.

And again, that's "Muhammad Ali" next Sunday, the 19th, premiering on PBS.

Thank you, everyone.

Thank you.

- [Ken] Thank you, Raina.

You were wonderful.

Thank you so much, Malcolm, Claressa.

- [Malcolm] Thank you guys for having me.

- [Ken] So great to be with you.

Be well, be safe.

- [Raina] Thank you again.

- [Claressa] Thank you guys for having me.

Appreciate you.

- [Raina] It was great.

Support for PBS provided by:

Corporate funding for MUHAMMAD ALI was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by David M. Rubenstein. Major funding was also provided by The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations,...